Seventy-five years ago

this Christmas, decorated trees, presents and singing carols were likely not on

the minds of Canadian troops caught up in the losing battle of Hong Kong. But it would certainly be a day they would

remember, and not particularly fondly, with a surrender to the Japanese the

order of the day. Far away from families and with an unknown future ahead of

them they had seen friends killed and wounded and at least heard about numerous

atrocities committed by enemy soldiers. Now seventy-five years later it’s

important that we remember too.

For those of us who had

relatives there in Hong Kong we have a very personal connection to that

Christmas of 1941. In my case, it was my uncle, Donald Penny, a Corporal in the

Royal Canadian Corps of Signals. I don’t

know for sure where Don was on December 25, 1941, but from the various accounts

I’ve read he was with a small RCCS unit attached to East Brigade providing

communications links between the Royal Rifles of Canada and Fortress

Headquarters. Fellow Signals NCO Ron Routledge later said in an interview,

“Surrender? Well, I recall being, well everyone had to, we had to stockpile all

our arms in one particular place in a field and wait for orders from the

Japanese...”

Any feelings of

uncertainty I have about my uncle’s whereabouts that day pale in comparison to

what his family must have been going through seventy-five years ago. They knew about the battle in Hong Kong but

had no idea if Don was alive, wounded or dead.

An article in the Vancouver Sun

from December 26th reflects the lack of information available to

family and friends back in Canada.

It wasn’t until

November, 1942 that Don’s family received official word that he was a Prisoner

of War. Weeks later he and his fellow

Canadian POWs would spend their first Christmas in captivity, most of them

half-starved and malnourished in Sham Shui Po camp on the mainland of Hong

Kong. On November 29th the camp received the first Red Cross parcel

distribution. As Signalman Walter

Jenkins said, “...we all would have died in Hong Kong, you know, if it hadn’t

been for the Red Cross.” One of my uncle Don's notebooks has a page showing the Red Cross parcel distributions while he was a POW.

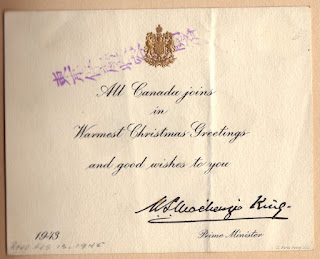

On Christmas Eve the men received their first official

word from home, a message from the Prime Minister, Mackenzie King:

The

Prime Minister of Canada requests the International Red Cross Committee to

convey to all Canadians in prisoner of war or internment camps, on behalf of

their relatives and friends in Canada, and also on behalf of the Canadian

government and Canadian people, heartfelt Christmas greetings and best of

wishes for the New Year.

The Prime Minister desires to

assure them, one and all, that the thoughts of the Canadian people were never

more of them and with them, than they are in the greetings they send at this

Christmas season, and in the Wishes they send for the New Year.

The men also received a

ten-yen note that could be spent in the camp canteen. Signalman Ray Squires called it a “Godsend”

buying among other things a half-jar of malt and codliver oil. Christmas dinner

was a huge improvement on their usual evening meal. Tins of “Meat and

Vegetables”, potatoes and even plum pudding were on the menu. Services in the church hall included singing

carols – a muted celebration to be sure, given the terrible conditions they

were enduring as POWs, but still a time filled with more pleasant thoughts of

home.

In early 1943, Don was

one of about 600 Canadians transported to Japan. He and a few other Signallers ended up in a

camp near Tokyo; they were to be used as slave labour in a shipyard. Christmas that year was described by Canadian

officer, Capt. John Reid:

Two small pine trees we got today

and some decorations. This day a holiday

was used for putting up decorations the men made themselves from scraps of this

and that, they even made a fireplace with an electric light in it; it looked

like a real fireplace, they made an amazing job.

One of Don’s mementos brought back from Japan was a mimeographed sheet of Christmas carols. On the

reverse side he had made some notes about that Christmas. His poignant letter home three weeks later put the Christmas celebrations into context.

By December, 1944, life

in Camp 3D had taken on a sense of anticipation. American bombers had begun

runs over the Tokyo area giving the men new hope for a return home. The arrival of more Red Cross parcels also

boosted morale. Preparations for

Christmas went into high gear. Secret orders went out for materials that could

be scrounged or stolen from the shipyard and turned into decorations. Again,

Capt. Reid described the scene:

Christmas

again this year was very successful – the men made very amazing decorations,

with streamers and fireplaces and santa clauses and so on – really amazing and

all made out of scraps gathered from here and there. In the morning we had white rice, a great

delicacy and soup with leeks and carrots and twenty kilograms of meat. The leeks to flavour it were a wonderful

delicacy. At noon each man had one loaf of bread with some miso paste. Leek soup, Christmas pudding – two parts

flour to one of sugar. For supper fish,

one hundred and twenty-five grams per man, white rice, soya soup, and sweet

beans with sugar and Christmas pudding.

Red Cross parcels arrived in the camp and were issued one per man on

Christmas eve. The Church Service and

Christmas carols on Christmas Eve, a concert by the orchestra and the Japanese

again came in Christmas afternoon and took photos.

Although

the trappings reflected the Christmas spirit, there was also a reminder of

their situation as POWs. On the wall

across the aisle from one large wreath, the men had hung an imitation scroll,

hand-lettered by Signalman Will Allister:

We said: “By Xmas ‘42

We know the war will all be

through.”

We said: “By Xmas ‘43

We know that we will all be

free.”

We said: “By Xmas ‘44

We know there will be war no

more.”

But now? “By Xmas ‘45

I hope to hell

we’re still alive.”

As

it turned out, not only were the men of the Signal Corps at Camp 3D alive, by

December, 1945 they would be back home in Canada celebrating a truly joyous

Christmas with their families.