In my uncle Don Penny’s letter home from Hong Kong in early December, 1941, he wrote, “This will be the third Xmas in a row that I have been away from home. It won’t seem the same over here as back home in Canada.” Of course, he had no idea what awaited him in the days, months, and even years ahead. As it turned out, he would not be with his family for Christmas until 1945. In those intervening years he would see the Christmas Day surrender to the Japanese, a bleak first Christmas as a POW in Hong Kong, and two additional Christmas Days in POW Camp 3D in Japan.

Here are a few items and stories from those years.

The only way families back home in Canada knew about what had happened to their loved ones in Hong Kong came via the newspapers and radio broadcasts. Official news from Canada’s Dept. of National Defence didn't come until almost a year later.

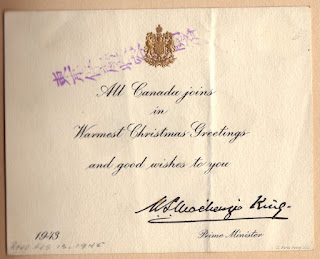

It was Christmas Eve, 1942 when the POWs received their first official word from home, via the International Red Cross. It was a message of Christmas greetings from the Prime Minister, accompanied by a card with a 10-yen note, money that could be spent in the camp canteen. The 25th was a day most like every other. However, the food was better than usual and there was a choral service and singing of carols.

Three weeks into 1943, Don and about 660 other Canadians were crowded onto a ship bound for Japan. He wound up at a POW camp near Kawasaki where the men were put to work in a shipyard. On the back of a sheet with the words to Christmas carols, Don wrote about his Christmas, 1943.

A greeting card from Canada and the Prime Minister for Christmas 1943, wasn’t delivered in Japan until February, 1945.

On December 24, 1944 at Camp 3D, each man received a Red Cross parcel. The “barrack” was decorated and as described by the Canadian medical officer Capt. John Reid, Christmas was a good day.

Christmas again this year was very successful – the men made very amazing decorations, with streamers and fireplaces and santa clauses and so on – really amazing and all made out of scraps gathered from here and there. In the morning we had white rice, a great delicacy and soup with leeks and carrots and twenty kilograms of meat. The leeks to flavour it were a wonderful delicacy. At noon each man had one loaf of bread with some miso paste. Leek soup, Christmas pudding – two parts flour to one of sugar. For supper fish, one hundred and twenty-five grams per man, white rice, soya soup, and sweet beans with sugar and Christmas pudding. Red Cross parcels arrived in the camp and were issued one per man on Christmas eve. The Church Service and Christmas carols on Christmas Eve, a concert by the orchestra and the Japanese again came in Christmas afternoon and took photos. (Capt Reid’s report, 1945, DND, Directorate of History and Heritage, File 593 -D17)

In his book, Where Life and Death Hold Hands, Signalman Will Allister described the poem that had been written on a scroll attached to the wall:

We said: “By Xmas ‘42

We know the war will all be through.”

We said: “By Xmas ‘43

We know that we will all be free.”

We said: “by Xmas ‘44

We know there will be war no more.”

But now? “By Xmas ‘45

I hope to hell we’re still alive.”

He, my uncle Don, and their fellow Signals at 3D did make it back to Canada for a joyful Christmas 1945. With all their experiences, however, Christmas would never be the same, and I always take a few moments at this time of year to think about those brave and steadfast young men. How fortunate we are today.